Getting Things Done

Click here to see what's on this page.

At the end of the day, having a problem or challenge implies a need to get things done. Many of the things we do day-to-day like grocery shopping or getting gas are things we both understand and know how to do. In fact, most of the things we get done are things we already know how to do. Learning new things is hard. Moreover, learning new things we’re not really interested in is really hard. Welcome to aging.

Housing & Getting Things Done

As a senior, our homes mean a lot. Carmen and I have suggested that your home reflects your “self.” As seniors it’s highly likely we’ve been in our current home or apartment for many years. Staying in our home is our number one concern. We don’t want to move. But what happens when staying in our own home gets challenging?

If it gets harder to shop at our grocery store of choice, we find a different grocery store. If the gas station we go to raises its prices, we find another gas station. However, if our houses our us – reflections of how we define ourselves, changing homes is a whole different story. You don’t get your “self” done. In other words, changing yourself is really hard.

You can select a senior housing facility based on a set of requirements, but you can’t select one easily based on your “self.” As we’ve suggested, until you’ve mastered the Five Master Techniques, you really don’t understand that there are only three ways to live: independent, assisted, and dependent. You’re still tinkling of your house as a reflection of you. Separating you from your house for most of us is like asking us to get a lobotomy. Ouch!

Keep this in mind as we discuss ways families can better move forward in addressing issues like housing.

Project & Task Management, Power & Transformation

That subhead has some big confusing words. We’ll define them below. We want to explore and understand these concepts as we investigated the following question: Why are Super Agers able to change their housing situation easier than non-Super Agers.

When Carmen and I first talked to Super Agers we found most had the characteristics below:

They seemed like good business people. Or highly functional parents. So we first thought they applied business skills like project management to housing decisions. The thought was Super Agers might also engage their entire families and organize them to help with projects. They then used this project management skill to navigate their families through a series of difficult issues, activities and tasks like making housing changes. We thought they might create an objective, assign tasks to children, have a weekly meeting, and manage the project until the objective was reached. However, the more Carmen and I investigated, the less we found this to be true.

What Do Super Agers Do For Housing & Finances?

We asked Super Agers and Non-Super Agers how they addressed areas where they had a fair amount of control like housing and finances. In other words, they could choose their housing environment and they could choose how to spend their money. Were they meeting with family members? Defining objectives and mapping out tasks?

Carmen and I were also used to working on projects and were familiar with the Project Management process. It seemed like a rational way to go about addressing serious issues like housing and finances. But the Super Agers didn’t plan by having family meetings or making project plans.

Super Agers & Housing

Instead, Super Agers looked to the community for information and guidance. For housing, they talked to providers (e.g., Del Webb, Brookdale, Holiday, etc.), met with friends in various senior housing environments, and attended meetings on housing topics at senior centers. In other words, they met with community organizations and community members. They didn’t discuss these issues with their children. What’s more, when asked, they specifically said they were;t interested in their children’s input.

Super Agers & Finances

Likewise, for finances, we discovered seniors met with providers (e.g., financial planners, brokerage companies, personal financial advisers, etc.) and discuss with their friends how they were addressing retirement finances. They didn’t meet with their family members. In fact, they told us they didn’t want their finances made public to their children. Their money was their money, not their children’s money. Of course, they all had plans to leave their children an inheritance. They just had little interest in enlisting their children in a responsibility they knew was theirs. Also, they did;t see their children as knowledgeable in age-related issues. Their kids were much younger. Also, their kids didn’t have their experience.

Super Agers Focussed On The Community

In these housing and finance, Super Agers were not Project Managers, but rather, Community Managers. They worked within their community and community resources to become knowledgeable on their own terms and in their own time.

Non-Super Agers Ignored Their Family

Unlike Super Agers, Non-Super Agers weren’t as aggressive in getting information and options about senior housing. In fact, they generally objected to personally seeking any information. Their family members often passed on literature and internet links. But this information was largely ignored. They tended to say they weren’t ready. When they were, they would know, and they would do something.

For finances, Non-Super Agers became stressed when discussing basic budgeting ideas. They almost all claimed that they didn’t overspend. We often heard quotes like “We’re too poor to overspend.” When asked if they had a prepared budget, the vast majority said no. The few that has a budget, didn’t track the budget against actual spending. Or they said they once did, but haven’t done so in a while.

For example, Non-Super Agers said things like “We know what we’re doing,” “we’ve been doing it for fifty years,” and “if we wanted our family’s help, we’d ask for it.”

How Children Of Seniors Get Involved

When Carmen and I had an opportunity to question the children of agers, they had a very different approach when addressing their parent’s challenges. Most children were drawn into their parents’ age-related issues during a crisis like hospitalizations, diagnosis of debilitating chronic conditions, and depletion of finances.

These children did not use community management techniques, they applied Project Management techniques to solve the crisis. In other words, it was a checklist, task list type approach. For example, if Mom broke her hip, what needed to be done? If Dad was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, what needed to be done? The kids made a list and gathered information for issues on the list. The kid’s approach was very different from that of their parents. The kids were Project Management oriented. Most also had busy lives full of their own challenges.

The children of seniors were making lists and gathering information, whereas their parents were focusing on getting better, ignoring their kid’s lists, and saying they’d get to the information later.

The differences in approach between parents and children created a lot of conflicts. The fact that it generally happened during a crisis only aggravated the conflict. As best Carmen and I could determine, children that were feeling constrained by time, money and their own children had limited patience. In other words, they wanted things addressed relatively quickly, and their approach was to make lists and tasks of what they thought would address the issue(s). Their parents also didn’t like this approach. They saw it as coercive and controlling.

A Parent In The Hospital Example

The Background

Mom (or Dad) has collapsed, been rushed to the hospital, and is diagnosed with a chronic condition. According to the Doctors, Mom is no longer able to function independently. The kids show up at the hospital, and in one form or another, ask Dad where they’re going to move. Dad says nowhere. He explains to the kids that he can help Mom. Although holding various levels of incredulity, each child asks Dad how he’s going to do all the things that Mom has historically done.

Things like cooking, laundry, and cleaning. One child asks up how he can do Mom’s work while being Mom’s caregiver. Dad says, “We’ll get by.” “How?” the kids ask? Dad has no plan. Just a feeling that they’ll be fine and will find a way. Some of the kids seem to acquiesce but others think Dad’s crazy. Dad has had a triple bypass surgery. He’s at least twenty pounds overweight.

A Child Panics

At least one of the kids is terrified of this new reality. Consequently, they develop a plan. They’ll identify options, gather information, and compare features and pricing. They’ll examine Dad and Mom’s finances. Also, they’ll seek any additional funding from the kids. They’ll bring Mom and Dad to different housing options. Additionally, they’ll even offer Mom and Dad the opportunity to move into their home. Finally, they’ll ask Mom and Dad to select their preferred option.

They call a family meeting to discuss their plan. One of the kids says they won’t attend. The others say they’ll try to make it. There seems to be some desire to meet, but not a lot of enthusiasm. The planner says it’s a must. “How can we not meet?” “Mom and Dad need us to intervene,” the planning child screams. One of the kids responds and says, “If it is so important to Mom and Dad, shouldn’t they be attending the meeting?” The planner agrees and asks Mom and Dad to attend. Dad and Mom say no. Not to discuss housing options. Not now. They’ll go home. Things will get better. Maybe they’ll talk about these things down the road.

What’s Really Going On?

What’s going on here? Why are the kids and their parents so at odds? First, it may not just be the parents and kids at odds. Very often, there is disagreement among the kids. But let’s simplify a bit and assume agreement among the kids so it’s kids versus parents. The parents believe they can stay home and the kids don’t.

Carmen and I believe the disagreement happens so frequently because of our perceptions of (1) autonomy and (2) risk. We point out in the Section on Born to Choose: Autonomy & Dissonance that we simply want to make our own choices, and because we are different people, with different perceptions, we often seek different outcomes. The other reason is the confusion over “risk.” As we point out in our Section on Housing, the notion of risk is perceived very differently between parents and kids.

Why Family Meetings To Address A Crisis Usually Fail

At first, Carmen and I thought every family would want to hold family meetings. The lack of family meetings struck us as unusual. We heard lots of reasons why including:

From this point of view, the lack of family meetings to discuss how and where an Ager will live makes perfect sense. It’s the same reason why teenagers don’t sit down with their parents and have a meeting to discuss what they’re really doing on Saturday night.

Community Management / Engagement

When it comes to care planning, Super Agers also don’t have family meetings. Instead, they chose to engage with subject matter experts and community members in key areas related to successful aging. Their approach most closely resembled an area known as the Community Organization/Engagement Model.

Before we start to discuss this thing called “Community Engagement,” Carmen and I need to ask you to consider a bit of history. Many things we think as common today, were simply unbelievable to generations past. American’s fought against compulsory education for children. Slavery was the norm and believed to be God’s plan. Voting was controlled by state legislators and granted only to land-owning white males because no one else could vote intelligently. Legal immigrants were considered appropriate for working but not for citizenship.

The Status Quo Is A Barrier To Change

The status quo is the status quo for many reasons. Many of these are connected to psychological, cultural, and sociological phenomena that have built up or been integrated into individuals and society for generations. For example, most people’s identities are tied to the status quo. Voting for example may define a person as an American. If I value the vote and don’t value you as my equal, why would I want you to vote? What does giving you the vote do to my perception of me? To my sense of identity? If I believe I’m American, and you are less, or at least someone that should be subject to my authority, why would I want to give you something that levels your rights with mine?

Historical Examples Of Bad Ideas, Institutionalized

Let’s look at a few of these historical issues. For example, in the early nineteenth century, the majority of Americans believed children’s education was their parent’s responsibility. Not an obligation of the State. Even teachers objected to mandatory education. In the nineteenth century, most Americans believed that legal Asian immigration and even rightful claims to citizenship were inappropriate because Asians weren’t like Americans. The Know Nothing Party fought for laws restricting Asians and immigrants.

In addition, the Chinese Exclusion Act prevented Asians from attaining citizenship. In the early nineteenth century, African Americans were still enslaved in many parts of the country. After the civil war, African American’s were vigorously fighting to realize gains in the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments to the Constitution, but most Americans were reluctant to grant these rights. Most state anti-miscegenation laws were not repealed until the middle 20th century. African Americans were simply considered inferior by most Americans. They weren’t worthy of being equal to white Americans. Prior to the twentieth century, most Americans didn’t think women should be allowed to vote. Even lots of women agreed that they shouldn’t have the vote. Today these beliefs are barely imaginable and considered racists, sexist and xenophobic.

The Wrong Things Often Become Institutionalized

Here’s the point: bad things get institutionalized and become part of the culture. When this happens it’s really hard to change people’s perceptions, and correspondingly, government policy. When things do change, it is almost always do to strange combinations of community advocates, private interests, and government officials that collaborate to create change. The change materializes over time as previously unempowered stakeholders become empowered, and resistant stakeholders start to accept the “new” ideas, programs, and policies.

Compulsory education started when educators, passionate community members, and politicians started working together to transform how people perceived education. In addition, rights for African Americans took abolitionists hundreds of years, required a civil war, protests from faith-based organizations, constitutional amendments and millions of citizens that believed black people were equal to white people to transform how people perceived African American rights.

Immigrant rights also required efforts of wealthy private citizens, the settlement movement, a notion of scientific philanthropy, and settlement houses to transform how people perceived immigrants. Securing a woman’s right to vote also took hundreds of years and involved passionate suffragettes, The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and The Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) to transform how people perceived a woman’s right to vote.

Guess what? Americans deal with aging issues like a relic of the past. A past with the following characteristics:

New Ideas About Aging Are Coming

As the examples above demonstrate, ideas and perceptions evolve over time. This means that our beliefs about staying in our own homes, fearing senior facilities, and not discussing end-of-life issues are likely to change over time. Our ideas will “Transform.” The information below is how these transformations happen.

Community Engagement

In our interviews with Super Agers Carmen and I discovered that this transformation was occurring through something resembling Community Engagement. One of the working definitions from Principals of Community Engagement defines the field as follows:

“…the process of working collaboratively with and through groups of people affiliated by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations to address issues affecting the well-being of those people. It is a powerful vehicle for bringing about environmental and behavioral changes that will improve the health of the community and its members. It often involves partnerships and coalitions that help mobilize resources and influence systems, change relationships among partners, and serve as catalysts for changing policies, programs, and practices”

Super Agers Seek Out Community For Transformation

For example, Super Agers reached out to communities or ecosystems possessing knowledge that could inform them of options. In housing, they aggressively reached out to senior communities, builders, and residents at these facilities to investigate options.

Similar to housing, in health, Super Agers became quick studies of ADLs and IADLs. For example, they often volunteer in senior centers or learn about what levels of self-sufficiency different senior properties target.

From a financial perspective, they met with financial planners and attended financial planning meetings. They also explored options that might help extend their financial resources like living with a child or having a child move back in with them. Also, they knew about long-term care, life insurance policies, prices of continuing care facilities, cost of in-home care, and government policies promoting aging in place. They learned how to optimize their financial resources.

As for end-of-life chores, they had good lawyers who understood estate planning and state Medicaid and Medicare laws. These lawyers knew how to transfer funds so that Agers would qualify for maximum government benefits while enjoying their savings.

Community Engagement Explained

The chart below is from community engagement programs. It demonstrates how to promote optimal outcomes when multiple stakeholders or communities are involved. The process creates one of awareness, exploration, collaboration, and ultimately empowerment. Carmen and I believe the reason this process works is because it allows the Ager to remain autonomous and self-directed while addressing scary issues. They reach conclusions on their own, over time, through knowledge and engagement with solutions. It’s the exact opposite of what happens when a child tells their parent they need to move and gives them a list of locations and times to visit.

The chart below shows how community engagement works. It’s slow and non-coercive.

The Community Engagement Model Transformation Tree

Here’s another diagram used in community engagement programs. The metaphor is a tree. We all must first have roots. These roots are our starting point. The trunk is what’s needed to grow the tree and is made up of relationships with the community and personal empowerment. With these, we can begin the transformation process.

The Roots

The root system represents the historical. For example, think of it as a kind of “as-is” state. It’s also how all realities emerge. From a rooted set of traditions.

The Tree Trunk

The trunk and the surrounding space represent the environment in which the tree can grow. For example, the more robust the relationships among the community, the greater the empowerment of those seeking transformation the greater the chance of a thriving tree. The threats and opportunities represent the reasons why and why not. Any change has proponents and opponents. Generally, the status quo resists change of any form. The opportunities are the ability to thrive, especially in a changing environment.

Crown Of The Tree

The robust flowering or leaves of the tree occurs when communities, institutions, and individuals are able to transform. The transformation enables them to address the new aspirations, goals, and objectives of the community.

The Community Engagement Model Transformed Into A Family Transformation Tree

The community approach is the method that more closely matches what Super Agers do to transform their historical beliefs into the beliefs more appropriate for aging. They’re able to shed prejudices, faulty assumptions, and gather needed resources for the last decades of their life.

The Roots

The root system represents the historical. Think of it as a kind of “as-is” state for families. The aggregations of childhood, family holidays and adult communication.

This manifests things in things like what family hosts a holiday, the foods prepared, and even sitting arrangements. It also covers how family members talk to one another, and even the subjects discussed. It’s the foundation of what families do and how they operate.

The Tree Trunk

The trunk and the surrounding space represents the environment in which tree can grow. The more robust the relationships among the family members (and any new community members that might support the transformation), and the greater the empowerment of these, the greater the possibility of transformation. Essentially the communities and being empowered to seek out the opportunities and push back the threats.

Crown Of The Tree

The robust flowering or leaves of the tree occurs when communities, families and individuals are able to transform. The transformation enables them to address the new aspirations, goals, and objectives of the Ager, the Ager’s family and the community supporting this transformation. The greater the transformation, the better the tree thrives. Super Agers followed the community engagement model and were able to transform their lives into ways that made sense to them, their families and the ecosystem supporting the transformation.

Project Management

Let’s jump back to Project Management. There is a tendency among anyone trained to solve problems, to solve problems the way they were trained. If you’ve worked in an organization and worked on a team, you’ve likely been exposed to Project Management. These may have included attending meetings where you discussed the project scope, necessary tasks and who might be the best person to perform the task. Or you may have simply been handed some of the outputs of the project management process like the project scope, a project Gantt chart of a project task list.

Why Project Management Doesn’t Work Well In Care Planning

There are many lessons to be gleaned from how project management is used in the workplace to define and complete projects. But you need to be very careful. Successful Project Management Processes require a very clear goal and scope. Part of the initiation of a project involves this definition. Carmen and I have suggested that this rarely happens between Agers and their children. Even when just the Ager(s) is in charge, (s)he may be unable to establish a clear goal and scope. There’s simply too much confusion and unknown outcomes for clear goals and objectives to be set.

Traditional Project Management Process

Housing & End-of-Life Issues Are Resistant To Clear Goals

When it comes to housing and health, Carmen and I discovered there are serious challenges for Agers when it comes to identifying any kind of a goal, much less a scope for that goal. Housing is the most obvious. We heard many stories before a hospitalization of how an Ager would know when it’s time to make a housing change. When we were able to reconnect with that Ager after a hospitalization, we almost always heard about their desire to age in place. It didn’t matter why they were hospitalized, or how dramatically the senior’s health had declined, or much why the questions were being raised. As an Ager, while we’re in the hospital or a rehabilitation facility, all we want is to get home. And when we do, we don’t want to leave.

Health is similar. Take the example of being hospitalized in our eighties for a fall. We break a hip and get sepsis in the hospital. With these health challenges, we’re literally on our deathbed. But when we get better, we’re happy to be well and don’t believe we have a debilitating health condition. Any outsider would question our ability to care for ourselves. But as an Ager, we know we can care for ourselves. After all, we were fine until we fell. We’re not going anywhere, not yet.

This is what makes goals and objectives so difficult to establish. As we age, almost all of us prefer moving targets. Targets on our terms. Not our children’s terms. Or our caregiver’s terms. Not even our Doctor’s terms.

Without Clear Goals, Projects Management Techniques Fail

If you can’t clearly define goals and scope, projects fail: almost every time. Let’s repeat this: if you cannot define a clear goal and scope, projects fail. That’s probably why Carmen and I didn’t observe or hear about the successful use of the Project Management Processes in health and housing-related areas. But there are Project Management tools and techniques that can be very useful if you have experience with them. The Project Management Process itself can be very useful under certain circumstances.

Some Techniques Of Project Management Are Still Valuable For Care Planning

Also, there are traditional ProJet Management inputs and outputs that most of us are familiar with that can also be useful. If used with the right people at the right times these can be very helpful in getting things done. We discuss the application of some of these in our Chapter on Tips and Techniques.

Carmen and I do want to cover some of these so you know what we’re talking about. For anyone seeking expert knowledge in Project Management process, we refer you to the Project management Institute (PMI) (https://www.pmi.org/)

The PMI sets the standards for the Project Management Process. We’ll use their definitions in the field of Project Management to maintain standard terminology. The PMI has a very comprehensive Project Management Program. Carmen and I will focus only on what most people can easily understand and deploy. And we’ll make some name modifications as we go along to help you better follow our logic.

PMI Tools & Techniques Are Helpful

The diagram below shows how PMI demonstrates a process progression using a set of “inputs,” informed by “tools and techniques” leading to a key outputs.

There’s something mercilessly complicated about PMI’s approach. But think of this analogy. Your child likes playing baseball. You sign them up for a league. They go through tryouts and get selected by a coach to join a team.

Here’s that scenario delineated in the PMI form above.

Or said a bit differently, the coaches determine the kinds of players they want for their team, observe the players at tryouts, and draft the players based on their goals, given player availability.

Some PMI definitions:

Tool:

Something tangible, such as a template or software program, used in performing an activity to produce a product or result.

Technique:

A defined systematic procedure employed by a human resource to perform an activity to produce a product or result or deliver a service, and that may employ one or more tools.

Input:

Any item, whether internal or external to the project is required by a process before that process proceeds. An input may be output from a predecessor process.

Output:

A product, result, or service is generated by a process. May be an input to a successor process.

Activity:

A distinct, scheduled portion of work performed during the course of a project.

When PMI Techniques Are Valuable

Project management tools and techniques are valuable. They are most valuable when there is a clear goal and set of requirements. Carmen and I see these skills invoked most aggressively when an Ager has “given up” their desire to stay at home. At that point, family can and often does aggressively move in and use project management techniques and tools.

Most of us have also been involved in other “project management” or “task” type environments. This is when a boss comes in and says, “Do this now.” Management by being bossy. There’s actually a theory around leadership and power. The theory identifies different types of power that leaders have to influence the behavior of others.

State of the art Project Management has become an all-encompassing process; one might even call it a kind of ideology. Whereas experts may be able to embrace Project Management as an ideology, the rest of us are most familiar with a few tools. We do things like make checklists, use Gannt charts (i.e., I need to sign up for Medicare, I first do X, then I can do Y, etc.) and apply expert judgment (i.e., I’m sending my son and his wife a gift card for Christmas because I saw the sweaters I sent last year on their Labradoodles).

Definition Of A Projects

The project management community defines a project as:

A project is a temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result. The temporary nature of projects indicates that a project has a definite beginning and end. The end is reached when the project’s objectives have been achieved or when the project is terminated because its objectives will not or cannot be met, or when the need for the project no longer exists. A project may also be terminated if the client (customer, sponsor, or champion) wishes to terminate the project. Temporary does not necessarily mean the duration of the project is short. It refers to the project’s engagement and its longevity.

Determining where an Ager should live seems like a perfect project. If it looks like a duck (project), swims like a duck and quacks like a duck, it’s usually a duck. But when you ask some basic questions like:

You find out that they have very complicated answers. Worse, the answer is very likely to change over time. Imagine you hire a lawyer to defend you against an alleged crime and halfway through the lawyer switches sides and now work to convict you and send you to jail.

In Care Planning, Roles & Objectives Get Confused By Context

Carmen and I observed dramatic shifts like this with Agers concerning housing issues. In determining where they’d live, at first, Agers were in control. “We’re the adults, we make the rules!” We heard comments from the kids like, “We’re being treated like we’re still kids, I’m fifty, we know what’s best for our parents.”

As the parent’s health declined, things started to change. They saw their parents break bones, hospitalized for dehydration, and fighting life-threatening infections like sepsis. The kids often described being in “a nightmare,” “banished to the basement while our parents run a household they can’t manage.”

Then at some point, the roles reversed. As parents succumbed to dementia or debilitating chronic illnesses, the kids took over decision making. The kids said things like, “Finally we get to do what’s best for our parents, it’s our house and we can get the help our parent’s need.”

In the case of moves, “We can finally make sure our parents move to where they can be safe.” Their parents didn’t share their children’s optimism. The parents said in private that their new living arrangement was like “being put in prison, relegated to the basement, locked up.” Many had their cars taken away. “We’ve lost our freedom,” was a common sentiment.

Fluctuations In Roles & Goals Minimize The Effectiveness Of Project Management Techniques

Swings like these make the project management process a real mess. We should note that if (1) you are a project management guru, (2) the Ager has a clear scope and goal and, (3) the Ager is on board with using a Project Management Process, you can make this process work. Because Carmen and I see the vast majority of Ager’s unwilling to set a clear scope and goal we do not recommend this process. But we do suggest you borrow some basic principles from the project management process under certain circumstances.

Carmen and I want to pay homage to the Project Management/Process community. For decades this community has been defining, testing, implementing and adapting processes, techniques, tools, and outputs to manage projects.

Best Times For Project Management Approach

Carmen and I have pointed out that Agers of all types face difficulty dealing objectively with aging issues. We point out that autonomy is a primary instinct for Agers, and autonomy is subjective.

Issues about where we live, how we feel, how much money we have and how we communicate with our family are all very personal, very subjective. Homes are the personification of who we are. Most Agers believe they will get healthier or feel the same in the future.

Agers have had decades of developing their “personal” communication style for family members. Without an understanding of “objectivity,” the Project Management Process fails. It fails because the goals and scope of the project cannot be defined.

There are times when this subjectivity is different. Times and situations when (1) the subjectivity turns into objectivity with a definable goal or (2) an activity needs completion.

Once A Specific Goal Is Identified, Project Management Techniques Work

Let’s look at an example. At some point, an Ager will look for a new home option. Remember, its only an option. The Ager may lead the search in good health. Or have it forced upon them after a medical or financial emergency and generally led by a child. In either case, once a goal is selected, a Project Management process (modified) is a great way of addressing the goal.

Keep in mind that the Ager may not agree to the ultimate option(s). They may want to stay at home. But the search for an option is the agreed-upon goal.

But there are project management tools, techniques, and outputs that are really useful in planning aging issues. We cover these below:

Project Management Tools & Outputs

Most people that have spent any time in an organization of over twenty people have participated in some kind of project management task. So it’s a natural place to turn for some kinds of challenges. If I need to make a housing decision, why not simply apply principles of project management and move forward?

Example 1

A married couple in their eighties lives in Wilkes-Barre Pennsylvania. The wife has been in good health and she has been able to take care of her husband, who is diagnosed with dementia. The husband, even with dementia, is strong and able to follow his wife’s directions. Together they’ve been able to manage the house, pay bills, manage complex medications, drive, cook and clean. They have two adult children, both married with their own children, in high school or starting college. One lives two hours away in Philadelphia the other in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Super Agers Approach

Super Agers addresses finance issues by hiring and following the advice of financial experts (e.g., certified financial planners, financial advisers provided through employers, presentations by experts at senior centers, etc.). Health issues were addressed with a plan developed in their fifties or sixties where they planned on downsizing and moving based on their ability and desire to manage complex housing issues (e.g., roof, lawn, trees, animal control, HVAC, windows, doors, plumbing, electric, insurance, remodeling, bathroom safety, etc.).

Alternative housing options were addressed by researching continuing care communities and senior villages. They also had criteria on when they would leave their existing home. The majority had drop-dead ages. They know beyond a certain age, usually by their early seventies, that if they hadn’t moved, it would be very hard to do so, at least on their terms. For end-of-life chores, all the Super Agers had an estate plan, advance medical directives, and power of attorneys. As for Family Communication, you guessed it, they had communicated it all to their children, caregivers and other relevant family members.

When we tried to tie back Super Ager’s behavior to family and caregiver communities, we didn’t see a lot of correlation to traditional project management techniques. In fact, if we focused on a fundamental necessity of project management what we found was fascinating.

Super Agers Had Non-Project Management Approaches To Addressing Their Challenges

Super Ager’s, however, only had an intuitive idea of what we would call requirements management. Traditional requirement management needs robust project requirements, the involvement of participants (i.e., users or people required to address the requirements), necessary resources, proper expectations, and management abilities. There are also critical to successful Project Management and Super Agers weren’t focused on any of these variables. They were focused on other things.

For example, what they seemed tuned to were the known unknowns. A NASA phrase made famous by a US Secretary of Defense. In other words, they knew what was coming even though they didn’t have much experience with these things.

Project Management Looks Like Care Planning, But It Is Problematic

The Section is part of Family Communication. Carmen and I thought a lot about this because there was an argument that the objective of Family Communication looked, in its ideal form, like project management. Project management is defined as the practice of starting, planning, executing, managing, and completing a project requiring a group to work together to achieve specific goals in specific time frames.

It Works With Professional And Nonprofessional CareGivers

Professionals are usually hired for a purpose. For example, they may rehabilitate, take vitals, or manage medication. In other words, they have a clear objective. In addition, caregivers usually have specialized training. They’re taught stuff. That stuff tends to get imparted. Doctors diagnose by asking questions, taking tests, and assessing the results. Likewise, home care providers gauge an Ager’s mobility and cognitive ability and provide interactions and care based on their assessment. Sometimes this takes place in a rigorous way, other times it’s more ad hoc. Regardless, the “goal” allows traditional project management techniques to be deployed effectively.

Families Don’t Have Proper Context

When families get involved, they also try and use their training to help. However, their training is often contextually inappropriate. Helping pick a proper home environment may be based on their experience when they picked a home for their growing family. They might have considered homes with enough rooms for the kids, a neighborhood with a good school system, and a price they could afford. But these were pretty much all their concerns. They didn’t call their parents, for example, and say here’s a list of what we need in a house, go pick one for us.

The skill of selecting an objective, creating criteria, and gaining consensus are still important skills that can help. You can use these skills when helping an Ager make decisions. In other words, tou don’t have to become a project manager or even understand the project or task management. But Carmen and I have managed hundreds of projects over the years and thought it is worth sharing a few things we learned.

Workplace Power: When home starts resembling a workplace

Carmen and I again choose to play pop psychologists and suggest that power relationships among family members are real and something worth considering. For example, power has been extensively studied by philosophers, psychologists, sociologists, and philosophers. Anyone who has ever been disciplined by a parent, from being grounded to being spanked, has experience with power. In addition, anyone who has ever had a boss, or been a boss, knows something about power. Therefore, we recommend you learn a little about traditional definitions of workplace power. With just a bit of knowledge, you can learn how to use it to help facilitate communication among family members.

Household Power Can Help Or Harm Care Planning

The definitions of workplace power include coercive (power to punish), referent (trusted and respected), expert (expertise), reward (ability to reward) and legitimate (a leader’s formal authority). Coercive power, for example, involves power exerted by people who can punish others. In the workplace, it might include refusing to approve your requested day off or giving you a poor performance review.

In family environments, we’re familiar with what often amounts to coercive power. For example, think of situations where one spouse needs to get an unwilling or reluctant spouse to participate in something like a family or community event. Maybe it’s a spouse’s mother’s Thanksgiving dinner and one spouse can’t stand attending and needs to be dragged to the event. Or maybe it’s a community event, like the opening of hunting season and one spouse can’t stand attending and is “coerced” into attending the event. However, the reluctant spouse knows that refusing to participate will result in some kind of punishment.

Default Power

For CarePlanIt purposes, we’ve noticed another area of power that is easy to recognize, but sometimes difficult to define. We’ll call it “default” power. Default power is the power to act when no other family member steps up to the plate. It’s usually someone who lives with or close by the Ager and isn’t the traditional family decision-maker.

You may have family dynamics where a family member is clearly an “expert” or has the ability to “reward” but another sibling is driving decisions. It almost seems that the decision-maker is making a decision because no one else has stepped up to the plate. Most people would recognize this as a kind of default position because no one else wanted it. There are strong arguments that this default person is better classified as one of the traditional five workplace power areas, but we’re keeping the “default” category because very often, another sibling can and does step in using their power to change the direction of an Ageing challenge. This is examined in Example 1 below.

However, Carmen and I don’t recommend you get carried away with Workplace Power structures. That’s because there is a built-in family power structure. Parents have “legitimate” power over their children. They created their children. This is forever. Keep this in mind.

We’re sharing Workplace Power structures because there’s a common area when an Ager’s housing environment starts to resemble a workplace. When our parents started reaching their eighties, things started changing.

How A Home Becomes A Workplace

I’ll use the example of my Mom and Stepfather. While living in the home where they raised their children, they reached a point where they had six people working for them on a regular basis. In other words, they had six workers plus them in the house. Consequently, there were eight people operating a household. If you’ve ever run or worked in a small business, eight people is not so small. For example, it’s the size of a small dentist’s or doctor’s office. Mom and Dad were not using most of these people full-time, but they were using them regularly.

At least half the people were there to compensate for age-related declinations. With all this going on in the household it also requires greater attention from the kids. In our situation, Carmen and I were concerned with so many people in the house and getting paid; something might go wrong. Once lots of people are in your parent’s home, concerns arise. We were not alone.

Concerns When A Home Becomes A Workplace

Many of the families we interviewed also had lots of people in their parent’s home and they had similar concerns. They included:

Workers not doing their tasks

Workers taking financial advantage

Borrowing money

Taking money or valuables

Stolen or missing medications

Carmen and I want to strongly note that in most cases there was nothing inappropriate taking place. For example, in half the cases, we’d even suggest that the people working in and around the house added extra value.

Managing Workers In The Home

This reality, however, did not deter family members from voicing their concerns. For example, some family members would routinely intervene and replace caregivers that asked for more money or too much time off. Family members would also fire workers when medications went missing medications, even without investigating if their own parents were abusing them (overusing their pain medication).

What Carmen and I observed was many households had turned into a workplace. When family members believed their parents were unable to effectively manage that workplace, they intervened. Family members would step in and try and manage certain aspects of the household, and Ager’s life. It involved areas around the five master techniques: finances, health, housing, end-of-life chores, and family communication.

In short, the household was functioning more like a workplace and this is when we observed Workplace Power relationships.

We’ll share two examples of how a home becomes a workplace, and workplace power analysis may help understand what’s going on:

Example 1 – Coercive Power

An Ager was in very poor condition. Physically she was bedridden most of the time. Cognitively she had good days and bad days: almost always a sign of some degree of dementia. A son had taken over managing financial affairs. A daughter was living at home and managing health-related issues, including caregivers.

When a valued caregiver asked for more money, the son said no. He had “coercive” power because he managed the purse strings. The daughter living at home was dependent on her brother releasing funds to manage the household, which in a way, benefited her. She had no power over her brother in this regard. The brother was the executor of the estate, and not only managed his mother’s day-to-day financial affairs, and in a way his sisters, but was also was responsible for any potential inheritance for the siblings.

Carmen and I saw lots of issues related to money. When an Ager was in their final years, we almost always saw the person that controlled the finances as the one with family power. When the household is being managed by lots of people, it can make some sense to view it as a workplace. If you want to have influence over decisions, obtaining one of the forms of workplace power can help. For example, power over money was consistently the most powerful force in these situations.

We also want to note that this power often stayed in the background until siblings disagreed over how money should be spent. Then this power was used by its holder to align their goals with actual expenditures or allocations. Prior to this use of coercive power, the daughter living at home would have thought she had the power: either Legitimate or Referent.

Examples Of Coercive Power Impairing Wishes Of Another Family Member

Here are a few areas where we observed this Reward and Coercive power intervening against the wishes of another family member:

- Home

- Maintenance

- Remodeling

- Caregiver

- Is one needed for example

- Price willing to pay

- Hours per day

- Need on weekends

- Transportation

- Maintaining a car

- Insurance coverage on car

- Who can drive the car

- Household Support (non-caregiver)

- Needed support

- Cost for that support

- Health Care

- Choice of Doctors

- Choice of treatments

- Locations of doctors

- Use of estate funds (funds governed by an estate plan)

- Moving funds out of trusts to support a beneficiary (e.g., spouse, caregiver for a spouse, etc.)

- Support for family members

- Using funds to help family members able to help a parent (e.g., plane tickets, hotels,

Money is used for so many things that whoever controls it ends up in a position to potentially intervene in lots of places. If we as Agers want our money used for certain things and in certain ways, for example, it’s very important that we make that clear in your estate documents.

Example 2 – Default Power

Often times a child or grandchild down on their luck, will try to get back on their feet by moving in with a parent or grandparent. We’ll call that person getting back on their feet Hope and the Ager, Angie. Hope also has a history of substance abuse and mental health issues. But hope is two year’s sober and is now living with Angie. Angie is in her eighties and needs assistance. However, Hope does the shopping, manages medications, pays bills and takes Angie to Doctor’s appointments.

There are several family members concerned about Hope living with Angie. For example, one of Hope’s aunts is concerned that Angie’s pain medications or money may be tempting to Hope. We’ll call the concerned aunt, Connie. Connie was actively involved with Hope’s recovery and has helped Angie in the past. By living with Angie, Hope has become the household power broker – by default. What CarePlanIt calls, default power.

Hope’s Default Power

It would be hard to classify Hope as deriving power from any of the traditional workplace categories. That’s why we added the default category. There are legitimate concerns about Hope.

Things concerned family members can do to observe the situation include:

Other Resources On Getting Things Done

Good article on community engagement here.

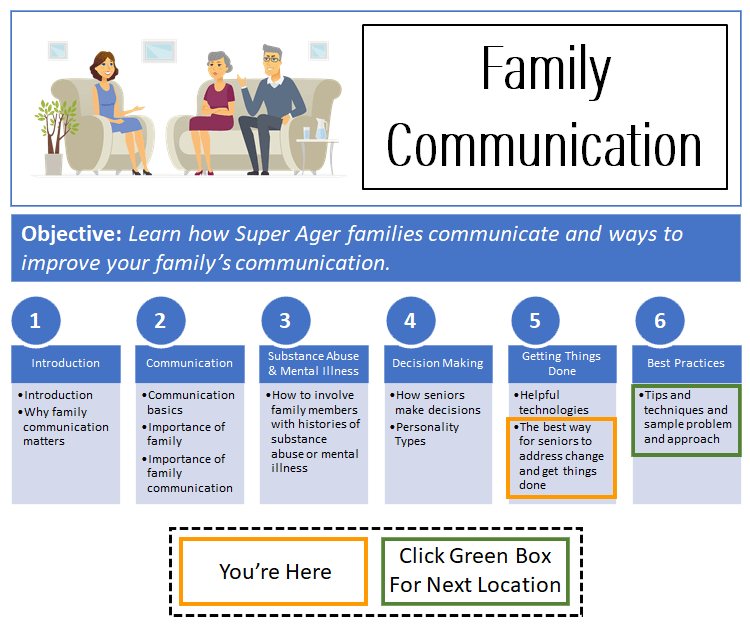

Make sure to also see our Best Practices: Tips and Techniques, here.